Aki LeggettCranes

Tall and graceful cranes are among the most ancient birds, yet out of the 15 species, 12 are listed as threatened under the IUCN Red List.

Among them, Red-crowned cranes (vulnerable status) can be sighted in my home country Japan. Conservation effort there particularly over the last 60 years has helped revive their population significantly from near extinction. In the UK where I live, grey Common cranes were once became extinct in the late 1500s but they too are making a good comeback thanks to protection of their habitats and reintroduction projects.

I chose to stand beside the “Cranes” for the following reasons.

The first and foremost is that they represent “Hope” for encouraging comeback. It is important to keep hope alive in the face of the frightening rate of biodiversity loss. Regardless of the species, some successful cases are based on co-operation among conservation groups and supporters, government, and local community including farmers and volunteers, which I think is crucial. We need to replicate similar effort wherever possible, no matter how small, before it becomes too late.

Second, restoring their wetland habitat directly contributes to increased biodiversity for other species such as insects, plants, and birds as well as carbon sequestration. Addressing biodiversity loss and climate crisis are at the core of the work of Highlands Rewilding Ltd set up by my husband.

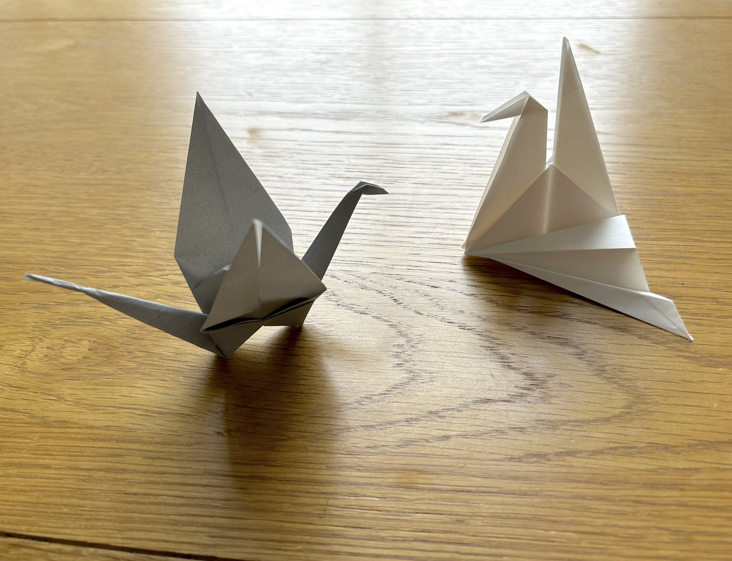

Thirdly, I personally have a deep cultural connection with them. Cranes are symbols of auspiciousness, beauty, and longevity in Japan. Most of us learn how to make origami cranes in childhood, and people make “thousand origami cranes”, in the hope that wishes will come true.

Cranes live on wetlands, grassland and marshes. In Northeast Scotland, new breeding pairs are sighted by RSBP recently in restored peatland for the first time. They mainly eat seeds, roots, insects, amphibians and small mammals, and are a part of a complex food chain and wonderful eco system of wetlands.

They face many threats. The main one is habitat loss due to agricultural and urban development, but also poisoning from pesticides, reduction of food availability and illegal hunting. In recent years, over-concentration in the remaining few suitable wintering grounds is reported, raising concerns for the risk of disease outbreaks. Climate change alters migratory patterns and breeding grounds, and legislation change could affect laws protecting wetlands.

At Bunloit estate by Loch Ness where I live and Highlands Rewilding operates, the team is working to restore peatland along with other nature recovery work. Scientists monitor biodiversity including bird population, and the results and issues have been communicated to feed into stakeholders, such as other conservation and research organisations, wider public, local community, and government bodies.

Personally, in addition to supporting relevant conservation organisations and doing what I can to keep desirable habitat for birds and insects in my garden and land, I intend to visit some of the sites where cranes are sighted to learn more. Luckily, after a long period of absence, increased numbers of successful breeding pairs of common cranes have been reported in Scottish Highlands, too.

As we face more devastating evidence of biodiversity loss and climate crisis, by standing beside the “Cranes” and supporting relevant activities, I would like to keep my hope high for them and all other species.